"How can we deconstruct the singular vision that is represented by one story? And how can we extrapolate from that single tile of vision to the mosaic of other human experiences and perspectives?"

-Deborah Appleman, Critical Encounters in High School English, 21

These questions clearly articulate the central task of critical reading. It is a two twofold task: First, critical reading requires the reader to take off her own glasses, to deconstruct the singular lens through which she views the text. Second, critical reading is a process of moving from this limited vision to postulate the perspectives of others in order to better understand the human experience.

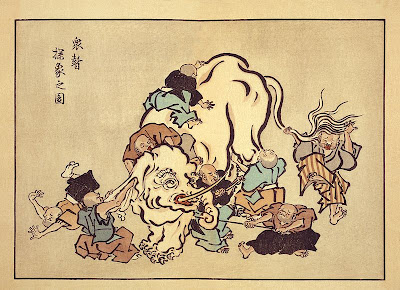

However, Appleman's description stops short of what it looks like to "deconstruct the singular vision." What happens afterward? Does the reader arrive at an understanding of the true ideas behind the text? If so, then critical reading is like the old story of the blind monks and the elephant. Each one feels a different part of the elephant and comes to a conclusion about what the object is, a spear (the tusk), a pillar (the leg), a brush (the tail), yet each perspective falls short of truly identifying the thing itself. Everyone else knows that the monks are touching an elephant, but blindness makes the monks' perspectives very limiting. If an authoritative meaning does exist, if there is an elephant in the room, then any other lens is invalidated and a philosophical deconstruction of the text, including a careful consideration of each more limited perspective, becomes the lone pathway to the truth.

On the other hand, maybe reading literature critically is more like chemistry than it is like feeling elephants. Maybe each perspective mingles with the text to make something entirely new. If this is the case, then literature is meant to teach us more about each other than it is meant to acquaint us with universal meaning.

In either case, an openness and awareness of other people's views is essential to reading, and I am glad for the chance to discover a means of teaching these concepts to adolescents through Appleman's book.

|

| Itcho Hanabusa - Blind Monks Examining an Elephant |

"O how they cling and wrangle, some who claim

For preacher and monk the honoured name!

For, quarrelling, each to his view they cling.

Such folk see only one side of a thing."

-Siddhartha Gautama

Eric,

ReplyDeleteYou are a very talented writer. I appreciated your effective use of allegory in this piece. However, I disagree with the idea that one reading takes away or invalidates another. Your chemistry metaphor is more apt. I particularly liked Appleman's metaphor of the sunglasses that don't change what it is you see, but make particular features easier to pick out.

I think that the challenge will be to teach the ambiguity of truth. To show students that have grown up in a culture of multiple choice scan sheets that there are multiple ways of knowing is certainly an uphill battle.

Thanks Paul.

ReplyDeleteThere is no doubt that the truth can be slippery, ambiguous.

Maybe the point I'm trying to make is that if there are multiple ways of knowing, they will always be limited so far as discovering the author's intended meaning. There will be certain things we will see that weren't really intended to be seen. In that way, the lenses Appleman describes are like a bad pair of glasses. They really will change what it is we see. At the same time, there will be things we can see that no one else can. This is where collaboration and critical theories become so valuable. Yet, if the author gets the final say on the meaning behind the text, our limited vision will always keep us from discovering precisely what he or she meant us to see in the text.

The exciting thing about literature is that it can take on a life of its own apart from the author. The reader is part of the process of discovering meaning, maybe even of constructing it. I mentioned earlier that this process teaches us about one another more than about universal truth. Thinking about it now, it seems that meaning becomes universally accessible only once the text has been emancipated from the author, once it becomes the possession of the reader. Collaboration and critical reading remain equally important in either case as we the readers (teacher and students) seek to discover the text's inherent value... and so we stumble upon the answer to a question we will undoubtedly be asked: "Why are we reading this anyway?"